Shirley the government can't be serious?

Economists are usually sceptical of governments getting into the business of owning and running commercial firms. Governments face complex and competing objectives, and this rarely leads to good outcomes. The experience of Air New Zealand in the 2000s, however, suggests that bad outcomes are not a given. If the Queensland Government acquires a stake in Virgin Australia, could it learn from the nationalisation of Air New Zealand? And could those insights have any broader relevance to Australia in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Grounded

On 21 April 2020, Virgin Australia—Australia’s second-largest airline—announced that it was entering voluntary administration. It was dubbed “Australia’s first big casualty of the coronavirus pandemic.”[1] Whilst it was true that the economic and travel shutdowns caused by the COVID-19 crisis had a devastating impact on its revenue streams, in reality Virgin Australia had been in trouble for some time. The company had posted large losses of $90 million or more in every year since 2013, and by 2020 was groaning under the burden of over $5 billion in debt.

In late March 2020, Virgin Australia had approached the Federal Government for a $1.4 billion loan but was rebuffed. Its major shareholders—many of whom were themselves airlines facing financial strain as a result of the global pandemic—also refused to inject new capital into the business. By early April, as it became clear that the airline was nearing collapse, many urged the Federal Government to take an ownership stake in the company to rescue the failing airline. The main arguments for doing so were firstly to maintain a viable competitor to Australia’s largest carrier, Qantas, and secondly to save thousands of jobs.

Whilst the Federal Government showed no interest in nationalising Virgin Australia, on 13 May 2020 the Queensland Government announced its intention to bid for a direct stake in the company via the Queensland Investment Corporation (QIC). Whilst the Queensland Government has indicated that its ownership of Virgin Australia would be at arm’s length through QIC, it has also made clear that its interest in the airline is motivated in part by wider policy considerations. For instance, the Queensland Treasurer has stated that:[2]

My number one focus as Treasurer is to retain and create jobs for Queenslanders, particularly as we move beyond the COVID-19 crisis.

We have been very clear. Two sustainable, national airlines are critical to Australia's economy. We have an opportunity to retain not only head office and crew staff in Queensland, but also to grow jobs in the repairs, maintenance and overhaul sector and support both direct and indirect jobs in our tourism sector.

Partial or total government ownership of airlines around the world is not rare. Some of those carriers are very successful commercially—Emirates and Singapore Airlines, to name just two. Others, however, have lamentable track records of safety and financial performance. For example, Air India, which is currently 50% publicly-owned, has accumulated losses over the past decade topping an eye-watering AU$14 billion (Rs696 billion).[3] When the Indian Government tried to sell its stake in the airline in 2018, not a single bid was received.[4]

Taking a broader view of costs and benefits

A benefit of public investment is that the government can take into account broader social costs and benefits. In the short-term, there might be some (net) benefits if investment can (i) deliver short-term financial stability (ii) preserve competition or (iii) maintain transport links that would otherwise be severed if a major airline were to fail. Transport links are essential to economic activity and losses of links can be very detrimental to communities.[5]

A key issue here is the counterfactual (the state of the world without the government investment). It might be possible to create a positive net impact on economic activity, particularly if the counterfactual is no service at all. In the short-term, this might require capital injections and financial stability, which only the government may be able or willing to provide in a time of crisis.

The benefit of government investment can also be its greatest weakness. By introducing objectives other than purely commercial objectives, it can destroy rather than create economic value—by allowing inefficiency to creep in. This means that taxpayers, who did not have a direct say in whether their money should be invested in the enterprise, may not get the best return on that investment.

Such problems may be manageable in the short run. However, the longer the government remains an investor, the greater the risk that such conflicting (and vested) interests may arise.

So, if the Queensland Government is serious about taking an ownership in Virgin Australia, how can it ensure that its investment delivers the potential benefits outlined above, rather than the disadvantages?

The Kiwi that learned to fly

One standout success story of government investment and ownership of an airline is Air New Zealand. In 2001, like Virgin Australia, New Zealand’s national carrier was on the brink of collapse. It had expanded aggressively throughout the 1990s into Asia and Australia, culminating in the full acquisition of Australia’s second-largest airline at the time, Ansett Airlines, in 2000.

Ansett was a larger company than Air New Zealand and required significant equity injections to upgrade the safety of its fleet. Ansett also faced growing competition from Qantas and Virgin Australia (which was known as Virgin Blue at the time). Unable to control ballooning costs, Ansett folded in September 2001. Air New Zealand posted a loss of NZ$1.425 billion for the year to June 2001, including an asset write-down of NZ$1.32 billion relating to Ansett. This led to Air New Zealand’s credit rating being downgraded to ‘junk’ status,[6] and its share price fell by over 80% between late August and late September 2001.

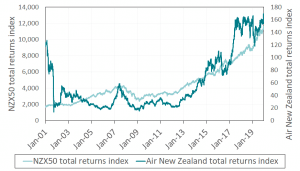

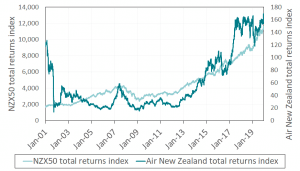

In October 2001, the New Zealand Government took an 82% ownership stake in the company at a cost of NZ$885 million. Over the next decade, Air New Zealand set about reorganising and improving its business model. The company returned to profitability in 2003, and posted a net profit after tax of NZ$290 million in 2019. Between October 2001 and December 2019, the total returns delivered by Air New Zealand stocks increased by nearly 12%, outperforming the New Zealand stock market (see Figure 1). In November 2013, the Government sold a 20% stake in the company, gaining NZ$365 million, leaving it with a 53% share.[7]

Figure 1: Air New Zealand and NZX50 total returns

The secret of Air New Zealand’s success

By almost any measure, the New Zealand Government’s intervention to bail out Air New Zealand has, with hindsight, turned out to be a success. The injection of much-needed capital stabilised the business. Moreover, knowledge that an investor with very deep pockets was now standing behind the airline gave other investors, including lenders, greater confidence in the company.

However, the real secret to Air New Zealand’s recovery was a change in the way the business was managed and governed.

Good governance

A new Board and management team was appointed, following the public acquisition of Air New Zealand. The new CEO, Ralph Norris, accepted the role on a number of conditions. The first of those was that the Government should stay out of operational decisions. Norris has stated that:[8]

We can't divorce business from the community. But that doesn't mean we should be any more obligated than any other commercial organisation in the country.....My job is to get on and run the business commercially - not as an arm of social policy. I wouldn't have taken the role if I'd seen Air NZ as an arm of Government. I'm here to steer this company around and I believe the relationship between management and the board will be good one.

This freedom from government interference allowed Air New Zealand’s management team to overhaul the company’s business model. The company adopted a low-cost airline model for domestic and trans-Tasman flights, relaunched a more focussed long-haul business and invested heavily in improving customer service.

The new management also reduced staff numbers significantly, and negotiated lower pay for remaining staff, in order to bring costs under control and return the company to profitability.[9] It seems unlikely that such restructuring would have been possible if the Government allowed itself to intervene in operational decisions.

Owner’s incentives

The Government was explicit when it took an ownership stake in Air New Zealand that it did not intend to remain a long-term investor in the business. For example, the Finance Minister at the time, Dr Michael Cullen, stated in parliament that:[10]

…any investment by the New Zealand government in Air New Zealand will ensure that there is effective control for a period in time but it will be subject to a clear message that the government does not see itself the long term shareholder in the company.

This meant that the Government was motivated to ensure that Air New Zealand would return to profitability quickly, and deliver as high a commercial return to taxpayers’ investment as possible. This clear objective made it possible for the Government to step back and allow the business to be run commercially. This appears to have been a successful approach even though the Government has ended up being a longer-term shareholder.

Market discipline

Another ingredient in Air New Zealand’s winning formula was that it remained a publicly-listed company. One of the most important benefits of being a publicly-listed firm is the availability of a stock price that embodies the market’s sentiment about the value of the business. If the market considers that the firm is performing well, the price will increase. However, if the market thinks that the firm is performing badly, the price will fall.

In Air New Zealand’s case, the availability of a share price would have given the Government a clear idea of what it could sell its shares for. But it also provided an important market discipline: Government intervening in the operations of the business in ways that may destroy value would be clearly visible.

Moreover, many of the owners of Air New Zealand’s listed shares were mum and dad investors, who also happened to be voters. Any meddling by the Government that destroyed value to those investors would not have been viewed favourably, come the next election. This was perhaps another factor that helped restrain any temptation by the Government to intervene in a non-commercial way.

Lessons for Australia

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented economic challenges for businesses in Australia and elsewhere. Now more than ever, governments may feel pressure to intervene by taking stakes in struggling firms that are viewed as somehow essential to the public interest. The airlines industry—and the story of Air New Zealand in particular—shows that government intervention of this kind need not destroy economic value.

The benefit that government investment or ownership brings, apart from major capital injections, is the ability to restore confidence to other investors that standing with them is a large, well-resourced investor who also has some skin in the game. This can be invaluable in restoring stability during a crisis.

The big risk with government investment is that this new, large investor will be motivated by considerations other than maximising returns—such as winning the next election—and that this investor will use its clout within the business to pursue non-commercial objectives that ends up destroying value.

The Air New Zealand case shows that if a government:

- treats its investment as temporary

- can provide the business with clear, unambiguous commercial objectives and

- can restrain itself from meddling in the day-to-day affairs of the business

then public investment can produce outcomes that benefit taxpayers as well as other investors. While there are no guarantees of success, the Queensland Government may well be serious…and don’t call them Shirley!

[1] BBC, Virgin Australia slumps into administration, 21 April 2020.

[2] Financial Review, 'Project Maroon': Queensland breaks cover in Virgin race, 13 May 2020.

[3] Business Today, Air India net loss at all-time high of Rs 8,550 crore in FY19, says aviation minister, 5 December 2019.

[4] The Hindu, Now, govt goes for 100% stake sale of Air India, 28 January 2020.

[5] See, for example, Frontier Economics, Airlines: Helping Australia’s economy soar, 9 September 2019.

[6] CNN, Air NZ hits back over Ansett collapse, 17 September 2001.

[7] Sydney Morning Herald, NZ government sells 20% of Air New Zealand for $324 million, 20 November 2013.

[8] Management New Zealand, Unfinished business: Why Ralph Norris is flying Air NZ, 4 April 2002.

[9] It was estimated at the time that 800 of Air New Zealand’s 9,300 staff would need to be made redundant in the first round of restructuring. New Zealand Herald, Job losses likely to hit 800 in Air NZ cutbacks, 9 October 2001.

[10] Response to parliamentary questions by Dr Michael Cullen, 3 October 2001.

DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

Making infrastructure investment more equitable and productive

Taxpayers will be dealing with the government spending that has been committed to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on the economy for many years to come. While there is a clear stimulus angle to infrastructure investment in the recovery period following the pandemic, value capture opportunities should not be overlooked. Moving to a beneficiary pays model will make infrastructure investment more equitable and productive.

Using value capture to fund infrastructure is popular among economists. By better aligning costs with beneficiaries, it promotes better decision making on the value of investment and is fairer for taxpayers. In a 2016 bulletin “Value Capture: Bypassing the Infrastructure Impasse”, we discussed the benefits of value capture mechanisms such as land uplift levies, the sale of development rights and change of use charges to help fund infrastructure in Australia. We also noted the reasons why, at that time, value capture wasn’t being widely used. In this follow-up bulletin, we discuss what has happened in the intervening years and why now, more than ever, value capture should be embedded in funding infrastructure projects.

To download this publication in full, click the button below.DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

Making a compelling business case

While we have an unprecedented pipeline of rail investment in Australia, it can still be difficult to justify rail investment on economic grounds through the Government business case process.

In this bulletin we explore why this problem arises and consider a broader economic narrative that should underpin most urban heavy rail investment. The bulletin also outlines the importance of carrying forward a base case from the planning phase to post-completion evaluation in order to robustly observe the marginal impact of a rail project and strengthen the evidence base.

A previous bulletin on Value Capture looked at addressing the broader infrastructure needs and aspirations of Australia through alternative methods of funding.

Why it’s hard to justify rail projects

Rail investment is hard to justify. It requires a large upfront payment in order to create an uncertain, long-term benefit stream. However, the current investment approval process doesn't do itself any favours. The key economic tool deployed to ascertain the economic merit of a potential public sector investment is a Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA). As the name suggests, this analysis compares the benefits associated with a potential investment to the cost of the investment. The key issue for rail is that the benefits side of the equation focuses on the direct impacts of the rail journey itself with relatively little emphasis given to the flow on economic benefits catalysed by a rail trip.

To continue reading this bulletin, click the button below.DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION